John Teramoto received his PhD from the University of Michigan. He is Curator of Asian Art at the Indianapolis Museum of Art.

Mike Lyon’s woodblock prints beg to be approached from a variety of different avenues. Lyon employs the latest tools and techniques in his production process including digital photography, electronic image editing, and most recently computer guided cutting tools — but in the end he produces each impression by traditional Japanese means — wood, pigment, paper, rubbing pad, physical exertion, and ultimately his eye and sensibility.

An American working in the United States, for decades Lyon has been a serious and dedicated student of various aspects of Japanese art and culture. He is also an avid collector of Japanese woodblock prints, or ukiyo-e. Because his works obviously conflate both Japanese and Western artistic traditions, I want to discuss them as such here. Moreover, as a personal response to Mike Lyon’s indigo prints, I wish to slant this essay in a more historical, rather than contemporary, direction.

From the very earliest stages of contact between Japan and the West in modern times (late 19c), Japanese art has exerted an influence on European and American artists; and the reverse was also true. Paintings by Edouard Manet (1832-1883) and Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) provide visual evidence of their fascination with ukiyo-e prints. Jean Millet (1814-1875) and Henri Rousseau (1844-1910) collected Japanese prints at every opportunity; and Japanese sensibilities affected the art of the American James Abbot McNeill Whistler (1834-1903).

Striking out for novel compositional modes and playing with new artistic visions, Japanese artists such as Kuniyoshi (1797-1861), Hokusai (1760-1849), and Shiba Kōkan (1747-1818), to name a few, incorporated the use of Western perspective and modeling in some of their works. But other than early Christian icons painted in Japan at the turn of the sixteenth century before its rulers closed Japan off to the outside world, paintings of a truly Western ilk did not appear in Japan until after the reopening of its doors almost 300 years later.

Returning the discussion to woodblock prints, artists like Yoshida Hiroshi (1876-1950) amd Kawase Hasui (1883-1957) created wonderful images that, as one author described it, were Western watercolors in a Japanese format. The perspective, drawing, and compositions were certainly familiar to Western eyes, but the sentiment remained distinctly Japanese. Along with artists like Yoshida and Hasui, the American printmaker Helen Hyde (1868-1919) and the Frenchman Paul Jacoulet (1896-1960) were creating yet another wonderful blending of traditions in their novel contributions to the world of Japanese printmaking by dealing with traditional Japanese subjects using traditional Japanese tools and techniques, yet producing works with a distinctive foreign flavor. Mike Lyon’s prints certainly act as an extension of this tremendous legacy.

Historically, the nude figure was never a traditional subject matter in Japan, but naked bodies can certainly be found in Japanese paintings and prints—especially in Edo period erotic prints. Emphasis, however, lay more on the physical and psychological interaction of the parties pictured and also involved the intended effect upon the viewer Portrayal of women in daily activities be it bathing or nursing a child also had voyeuristic connotations in which robes were dropped to the waist, long legs displayed, or their bodies totally nude entering a tub.

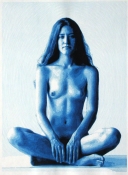

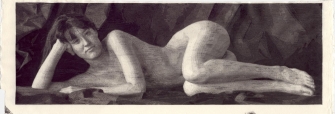

Looking at related images in Lyon’s prints, his models are for now undeniably recognizable as contemporary. In “Dana” (cat. 3) with her erect seated posture or “Rachel,” (cat. 9) with a lilt in her stance, the idea of “now” is augmented through hairstyle and a difficult to define yet definitely perceptible modern attitude. The latter comes across yet more engagingly in “Jessica,” (cat. 6) or the reclining nude (cat. 12) with head propped on her bent arm and her gaze fixed on the viewer (although we may have seen those eyes before in a painting by Manet).

On the other hand, there are elements that certainly transcend the boundaries of time. The portrait of the young man (cat. 14) takes one back to Classical antiquity as does the woman with outstretched arms (cat. 7) who could be a miniature figurine from ancient Babylon. Lyon’s wonderful print of mother and child (cat. 10) captures a scene repeated since the dawn of man.

The emergence of indigo prints, or in Japanese called ai-e (eye-eh), is often attributed to the passage of sumptuary laws that forbade the creation of polychrome prints, but evidence indicates that artists like Hokusai were already making indigo prints before the promulgation of the ban. Indigo dyed textiles were at one time limited to the aristocracy. Later however, the situation was entirely reversed, and indigo became the color associated with the common working man. Popularly associated with folk textiles, the color is deeply ingrained in the Japanese mind, and its selection was a conscious choice for Lyon.

Returning once more to the interplay between East and West that has spawned so many innovative movements in art, Mike Lyon’s figure studies in blue and gray recall the tonal figure treatments of artists like Thomas Dewing (1831-1958) and Whistler, who themselves were deeply enamored with Japanese art. The interplay of highlights, multiple gradations of blue and white imbue the figures with a luminescence that can quickly fade to darkened caverns. The soft, vibrant outlines of his forms—at times emphasized through contrast with hard edges—contribute to this sense of aura. Moreover the contoured patterns reminiscent of a geological formation, or the rippling edges of a pool of liquid light create fascinating visual effects. Lastly, the overprinting of wood grain adds to the sense of an outward radiating aura.

The ability to evoke auroras of the past in contemporary imagery imparts to works additional depth that resonates beyond the immediate presentation of form and meaning. When manipulated ineptly, nostalgia can easily lead to saccharine kitsch. It is preferable when that evocation emerges in and of itself from the object rather than in the manner of a calculated conceit. As beautiful modern images, Mike Lyon’s indigo woodblock prints make no pretense to antiquity. Yet they certainly are in possession of elements that impart to them aspects of timelessness. We look forward to where this fortuitous blend of cultural sentiments expressed through skilled hands and seen through penetrating eyes will lead next.

John Teramoto, PhD

Associate Curator of Asian Art

Indianapolis Museum of Art

Mike Lyon’s woodblock prints beg to be approached from a variety of different avenues. Lyon employs the latest tools and techniques in his production process including digital photography, electronic image editing, and most recently computer guided cutting tools — but in the end he produces each impression by traditional Japanese means — wood, pigment, paper, rubbing pad, physical exertion, and ultimately his eye and sensibility.

An American working in the United States, for decades Lyon has been a serious and dedicated student of various aspects of Japanese art and culture. He is also an avid collector of Japanese woodblock prints, or ukiyo-e. Because his works obviously conflate both Japanese and Western artistic traditions, I want to discuss them as such here. Moreover, as a personal response to Mike Lyon’s indigo prints, I wish to slant this essay in a more historical, rather than contemporary, direction.

From the very earliest stages of contact between Japan and the West in modern times (late 19c), Japanese art has exerted an influence on European and American artists; and the reverse was also true. Paintings by Edouard Manet (1832-1883) and Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) provide visual evidence of their fascination with ukiyo-e prints. Jean Millet (1814-1875) and Henri Rousseau (1844-1910) collected Japanese prints at every opportunity; and Japanese sensibilities affected the art of the American James Abbot McNeill Whistler (1834-1903).

Striking out for novel compositional modes and playing with new artistic visions, Japanese artists such as Kuniyoshi (1797-1861), Hokusai (1760-1849), and Shiba Kōkan (1747-1818), to name a few, incorporated the use of Western perspective and modeling in some of their works. But other than early Christian icons painted in Japan at the turn of the sixteenth century before its rulers closed Japan off to the outside world, paintings of a truly Western ilk did not appear in Japan until after the reopening of its doors almost 300 years later.

Returning the discussion to woodblock prints, artists like Yoshida Hiroshi (1876-1950) amd Kawase Hasui (1883-1957) created wonderful images that, as one author described it, were Western watercolors in a Japanese format. The perspective, drawing, and compositions were certainly familiar to Western eyes, but the sentiment remained distinctly Japanese. Along with artists like Yoshida and Hasui, the American printmaker Helen Hyde (1868-1919) and the Frenchman Paul Jacoulet (1896-1960) were creating yet another wonderful blending of traditions in their novel contributions to the world of Japanese printmaking by dealing with traditional Japanese subjects using traditional Japanese tools and techniques, yet producing works with a distinctive foreign flavor. Mike Lyon’s prints certainly act as an extension of this tremendous legacy.

Historically, the nude figure was never a traditional subject matter in Japan, but naked bodies can certainly be found in Japanese paintings and prints—especially in Edo period erotic prints. Emphasis, however, lay more on the physical and psychological interaction of the parties pictured and also involved the intended effect upon the viewer Portrayal of women in daily activities be it bathing or nursing a child also had voyeuristic connotations in which robes were dropped to the waist, long legs displayed, or their bodies totally nude entering a tub.

Looking at related images in Lyon’s prints, his models are for now undeniably recognizable as contemporary. In “Dana” (cat. 00) with her erect seated posture or “Rachel,” (cat. 00) with a lilt in her stance, the idea of “now” is augmented through hairstyle and a difficult to define yet definitely perceptible modern attitude. The latter comes across yet more engagingly in “Jessica,” (cat. 00) or the reclining nude (cat. 00) with head propped on her bent arm and her gaze fixed on the viewer (although we may have seen those eyes before in a painting by Manet).

On the other hand, there are elements that certainly transcend the boundaries of time. The portrait of the young man (cat. 00) takes one back to Classical antiquity as does the woman with outstretched arms (cat. 00) who could be a miniature figurine from ancient Babylon. Lyon’s wonderful print of mother and child (cat. 00) captures a scene repeated since the dawn of man.

The emergence of indigo prints, or in Japanese called ai-e (eye-eh), is often attributed to the passage of sumptuary laws that forbade the creation of polychrome prints, but evidence indicates that artists like Hokusai were already making indigo prints before the promulgation of the ban. Indigo dyed textiles were at one time limited to the aristocracy. Later however, the situation was entirely reversed, and indigo became the color associated with the common working man. Popularly associated with folk textiles, the color is deeply ingrained in the Japanese mind, and its selection was a conscious choice for Lyon.

Returning once more to the interplay between East and West that has spawned so many innovative movements in art, Mike Lyon’s figure studies in blue and gray recall the tonal figure treatments of artists like Thomas Dewing (1831-1958) and Whistler, who themselves were deeply enamored with Japanese art. The interplay of highlights, multiple gradations of blue and white imbue the figures with a luminescence that can quickly fade to darkened caverns. The soft, vibrant outlines of his forms—at times emphasized through contrast with hard edges—contribute to this sense of aura. Moreover the contoured patterns reminiscent of a geological formation, or the rippling edges of a pool of liquid light create fascinating visual effects. Lastly, the overprinting of wood grain adds to the sense of an outward radiating aura.

The ability to evoke auroras of the past in contemporary imagery imparts to works additional depth that resonates beyond the immediate presentation of form and meaning. When manipulated ineptly, nostalgia can easily lead to saccharine kitsch. It is preferable when that evocation emerges in and of itself from the object rather than in the manner of a calculated conceit. As beautiful modern images, Mike Lyon’s indigo woodblock prints make no pretense to antiquity. Yet they certainly are in possession of elements that impart to them aspects of timelessness. We look forward to where this fortuitous blend of cultural sentiments expressed through skilled hands and seen through penetrating eyes will lead next.

John Teramoto, PhD

Associate Curator of Asian Art

Indianapolis Museum of Art