Bill North is Senior Curator of the Beach Museum of Art. He has written extensively on the art and artists of Kansas and the region, producing numerous exhibitions catalogues and related publications for the museum. He curated the 2009 exhibition of Lyon’s prints and drawings and wrote the following essay for the printed catalog which accompanied the show.

Figuring It Out

by Bill North

Mike Lyon’s recent, large-scale prints and drawings are the result of his inventive adaption of digital technology and robotic machinery. The artist’s work also testifies to his keen interest in Japanese aesthetics and printmaking techniques. (Lyon has an abiding passion for Japanese art and culture and is an avid collector of Japanese ukiyo-e prints, a selection of which is included in this exhibition.) Lyon is not seduced by the bells, whistles, and whiz-bangness of digital technology. Computers and machines are among the many tools in his kit, much like paintbrushes or drawing implements. They are the means by which he seeks to realize his conceptions by moving directly from his mind to the object. Or, as he is fond of putting it, “Look Ma, no hands.”

Background

Lyon recognized the utility of computerization long before he applied it to his art making. The artist earned a BA in architecture and fine art from the University of Pennsylvania (1973) and a BFA in painting from the Kansas City Art Institute (1975). In 1976 he went to work for the family business, a Kansas City cattle hide processing operation his great-great grandfather started. There Lyon invented a computerized system to automate the labor-intensive process of grading cattle hides. His system enabled a team of four graders to enter information about a hide’s condition using a touch-sensitive console. The data was then compiled and tabulated by computer, providing nearly instantaneous results. Prior to Lyon’s innovation, the data was recorded, compiled, and tabulated by hand, an extremely time and labor-intensive process. In 1978 Lyon founded Grading Systems, a computer hardware and software design business. Under his direction, Lyon’s company developed ROBO-PIC, a computerized system for automating order fulfillment in large warehouses. ROBOPIC worked by using remotely controlled dispensers to place items in containers moving along a large conveyor belt. Grading Systems was highly successful and counted companies such as Tupperware among its clients. Lyon sold the business in 1991 and returned to his studio the following year. For the first time in fifteen years, he dedicated himself to making art full time.

Printmaking

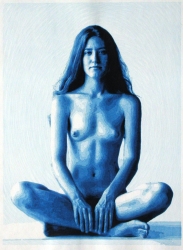

Jessica (fig. 2), a color woodcut created in September 2003, typifies Lyon’s work of the period. Woodcut is a method of relief printmaking in which the image is printed from the areas of the block’s surface that have not been cut away. The artist created the print as part of a demonstration while teaching a class on Japanese woodblock technique at the Center for Contemporary Printmaking in Norwalk, Connecticut. Lyon’s print is ōban-sized, a standard, traditional Japanese format, approximately fifteen by ten inches. Jessica was printed in blue from a hand-carved cherry block. The Japanese woodblock technique of repeated printings in shades of blue is known as aizuri-e (blue printed pictures). Aizuri-e prints were popularized in Japan in the 1820s with the availability of Prussian Blue, a stable and lightfast synthetic pigment imported from Europe.

Lyon printed Jessica using a baren, a traditional Japanese tool made of bamboo leaves wrapped around a disk. Paper is placed on top of the inked block, and pressure is applied by rubbing the baren on the paper’s backside. This technique allows for a range of expressive possibilities. How the color is applied and wiped on the block, variations in the degree of pressure applied, and variations in the baren’s motion all contribute to the final printed result. For example, in printing Jessica, Lyon tipped the baren slightly to create subtle gradations of color (baren bokashi) to provide a rich backdrop for the figure.

Two aspects of Jessica’s creation are not related to traditional Japanese methods. The print, like all of Lyon’s recent figurative prints and drawings, is based on a photograph. And, unlike ukiyo-e woodcuts, which are printed from multiple blocks, Jessica was printed from a single block using a method known as reduction woodcut. This challenging technique involves creating an image by carving and printing the block in stages. Portions of the block are carved and printed. More areas are carved, and the block is printed again on top of the initial printing. This process of reprinting the successively reduced block is repeated until the accretion of printings yields the desired image.

The ShopBot

Lyon’s innovative developments in automation with Grading Systems and ROBO-PIC are conceptual forebears of his current working methods. In spring 2004 the artist acquired a ShopBot CNC (computer numerically controlled) router, a large machine designed for woodworking applications (fig. 3). Coded instructions control the movement of the ShopBot’s router bit along the X (length), Y (width), and Z (height) axes. Lyon struck on the idea of adapting the ShopBot to carve his blocks. He developed a program to extract the information contained in a digital photographic file and convert it to a format the ShopBot understands.* Lyon programs the machine to carve blocks to his specifications, instructing it how far to move the router bit along the X, Y, and Z axes for each cut in the block’s surface. Automating the process in this way enables him to produce larger, more complex, photographically based images.

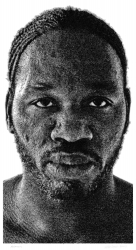

Lyon’s Anthony (fig. 4), a color woodcut completed in April 2004, is the first print the artist created with the ShopBot. Like Jessica, this psychologically penetrating portrait is based on a photograph and printed in blue. Instead of printing from a single, successively reduced block, Lyon printed Anthony from fifteen cherry plywood blocks. Conceptually, though, he approached Anthony as a reduction woodcut.

On each successive block, the carving of the preceding block was essentially duplicated before the additional reduction. Recalling the tradition of Japanese ōkubi-e (bighead picture) images, the subject’s head is placed close to the picture plane and fills the frame. This is a format Lyon has favored in recent prints and drawings. In Anthony photographic verisimilitude is mediated by the artist’s sensitive printing, imbuing the subject with a monumental yet human presence.

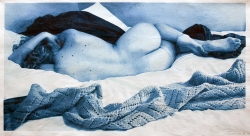

Since Anthony, Lyon has applied the same method to create prints of increasing complexity and scale. His color woodcut Sara (Sara Reclining) (fig. 5) of 2006 was printed from seventeen blocks and is forty-two by seventy-seven inches. Iwano Ichibei, a papermaker designated as a Japanese Living National Treasure, made the paper especially for Lyon. Working on this scale presented challenges for Lyon that required innovative solutions. He designed and manufactured a complex, large-format woodblock printing press with a five by ten feet bed (fig. 1). Before printing, the paper must be dampened in a humidor drawer. To carefully deliver the sheet from drawer to press and back with the printing of each block, Lyon built a system adapting components of an electric garage door opener. When operated, the drawer cantilevers over the press bed (closing the garage door). As the drawer retracts (opening the garage door) the paper is gracefully laid on the block’s surface.

In the spring of 2006 Lyon began creating large-scale, photographically-based pen and ink drawings using the ShopBot. After many unsatisfactory attempts to retrofit the router assembly with an ink pen, he was able to successfully make a giant drawing machine.

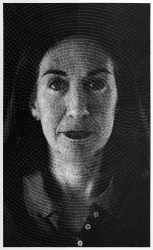

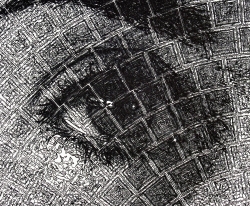

As with his woodcuts, Lyon programs the ShopBot with data extracted and converted from digital photographic files to instruct the machine how far to move the ink pen along the X, Y, and Z axes for each mark. The enormous drawings produced in this manner comprise many layers of intricate marks and require substantial amounts of programming and time. A portrait of the artist’s wife, Linda (front cover; figs. 3, 6, & 7), for example, at seventy-seven by forty-six inches, took over 12 million lines of code and eleven days of nonstop drawing.The artist and the figure

Recently, Lyon was asked “What draws you to the figure?” Below is an excerpt from his response.

This is quite natural for all of us, I think. We’re just wired that way. As infants, we nurse at our mother’s breast and gaze up at her face. We’re helpless and vulnerable and during our first years we depend entirely on our parents’ good will and love and care. We can’t survive alone. Almost immediately we become attuned to the subtlest nuance of posture and expression and quickly learn how to get what we need – attention, affection, warmth, sustenance, admiration, a wipe. We’re less likely to survive our first few years if we are insensitive. As adults, we (almost all of us) remain extremely sensitive to the moods of those around us – we know right away when someone’s angry, hurt, embarrassed, happy, available, etc. Our antennae are always unconsciously quivering.

Faces, in particular, hold my interest so much. Especially a certain ambiguity of expression which echoes in my mind as I automatically try to sense, is this person angry, interested, anxious, dismissive, dangerous, appealing, or what? I love faces. Love my mother’s face. My wife’s, yours. It’s the first place I look. The window to the soul. Total fascination. Switching gears for a moment to discuss process… For purposes of my work in woodblock printmaking and, the past five years, with machine assisted drawing and painting, there are some practical considerations in choosing images. First and foremost the person and the image (in this work I’m working from photographs I make and use as sources for my images) has to cry out to be Art – if a friend’s appearance speaks to me that way, I ask them to model. Often they’ll agree. Then, usually in my studio where I’m familiar with the way light streams in through my big east-facing windows, I’ll take several hundred digital photos (I used to use film, but digital is much easier and less expensive) while we chat. Then I spend a week or more pouring through them to select one (sometimes two) which really beg to become art. I first run through them and abandon the obvious rejects. My selection process is something like having your eyes checked, “which is better, A or B?” I keep the choice and abandon the other, compare with the next, and so on until I have three or four which seem to be possibilities. Throughout, I have in mind my process and its limitations, so I’m looking for images which are ‘suitable’ – that means they have to have areas of great detail, where I can really dig in and make something interesting – that really has more to do with pores, wrinkles, lots of small areas with large color or value changes – these lend themselves best to my processes. If these characteristics don’t exist and the image is really evocative, I’ll ‘cheat’ and create the sort of granularity I want to evaluate. Anyway, it’s impossible, really, for me to explain my aesthetic sensibility – it’s completely unconscious – I like it or don’t much – it’s magic, that’s all. Inexplicable.

…what draws me to the figure? I just love looking at people, I guess – simple as that.**

* Digital photographic files use a data structure known as raster graphics, which describes images in terms of pixels. When scaled to increased dimensions, raster-based images suffer a loss of resolution and quality. Vector graphics represent images using geometrical primitives such as points, lines, curves, and polygons and thus can be scaled without any loss of resolution. Lyon’s method involves converting a digital photograph to a vector file and using the vector data to instruct the machine how far to move the router bit along the X, Y, and Z axes for each cut.

** Mike Lyon, e-mail message to author, February 26, 2009.