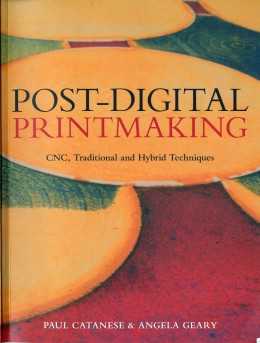

Excerpted from

Excerpted from

POST DIGITAL PRINTMAKING

CNC, Traditional and Hybrid Techniques

A&C Black Publishers, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing, Plc

(pages 119-128)

Chapter 10 MIKE LYON

The ink is what makes the image… regardless of what made the marks, the paper has no knowledge of parts of the block that don’t hold ink -to the paper, they’re invisible.

— Mike Lyon

Mike Lyon is an artist living and working in Kansas City, with an extensive body of works on paper that make use of CNC machinery. With two degrees in fine art, expertise in moku-hanga (Japanese woodblock printing), and several decades’ experience in developing computer-controlled electro-mechanical systems for factory automation, Lyon is uniquely positioned within the context of post-digital printmaking. As with many individuals with interdisciplinary backgrounds, it is difficult to summarize Lyon’s creative practice, the diversity of his influences and the depth of his research.

An accomplished artist and engineer, Lyon’s facility for investigating creative outcomes for new technologies pervades his endeavors. During his studies in the 1970s, exposure to computer-generated images such as Studies in Perception No. 1 by Leon Harmon and Ken Knowlton, as well as the processes used in the artwork of Chuck Close, had a great influence and still resonate with him today. Perhaps the most sustained source of inspiration for Lyon is Japanese Zen philosophy, modes of creative production, and visual aesthetics gained through years of study. A devoted collector of ukiyo-e, with prints dating from the 17th century, Lyon is also a high-ranking black belt in Shotokan karate and owns the dojo where he teaches martial arts. His absorption of Japanese culture within daily life has influenced his thoughts about image-making, resulting in a contemporary reflection on human nature through prints, paintings and drawings.

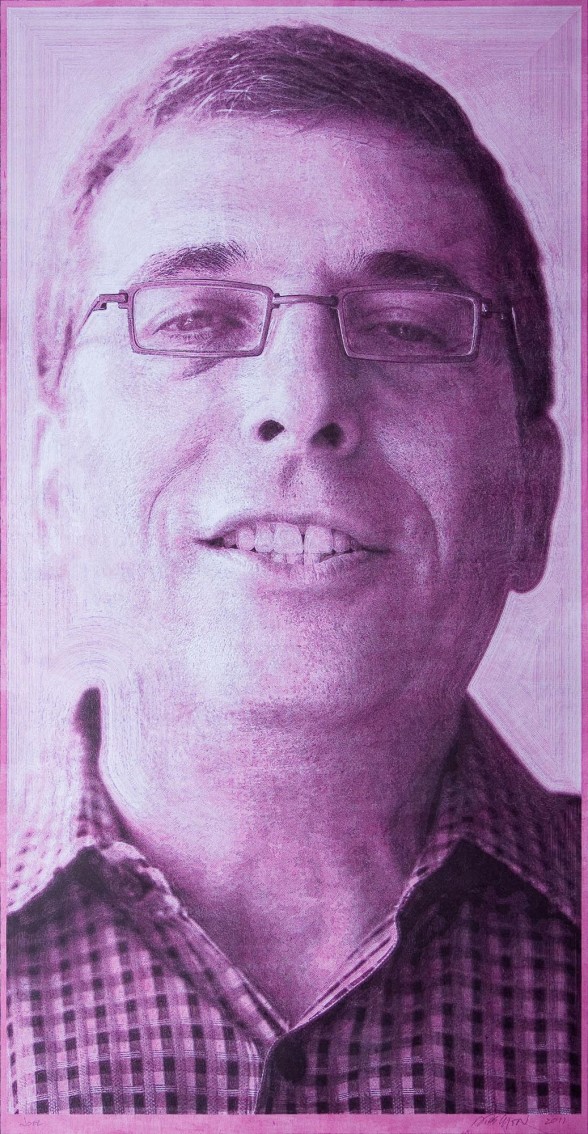

Figure 161. Mike Lyon, “Sara”, 2006. Size: 107 x 195.5 cm (3 1/2 x 6 1/2 ft). 17-block woodcut, printed in edition of ten. Permanent collection, Mirianna Kistler Beach Museum of Art. Image courtesy of the artist.

Figure 162. leon Harmon and Ken Knowlton, Studies in Perception No. 1, 1966. Size: 152 x 366 cm (5 x 12 ft). Image courtesy of Ken Knowlton.

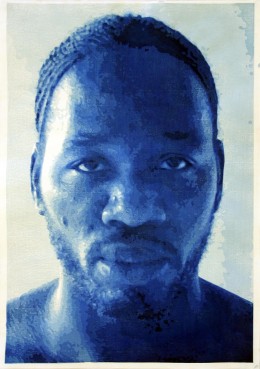

Figure 163: Mike Lyon, “Anthony”, 2004. Size: 76 x 53 cm (30 x 21 in). 15-block woodcut, printed in an edition of 13. Permanent collection of McNeese State University. Image courtesy of the artist.

Lyon practiced moku-hango for years, developing a workflow that allowed him to integrate photography with hand-carving, a process that he later adapted to generating CNC tool-paths. Over time, he gained expertise in carving and printing images with ten, 20, 30 or more woodblocks in tight register -a physically demanding process that required weeks of carving. While visiting Japan in 2003, Lyon was invited to stage a solo exhibition the following year at the Ezoshi Gallery in Kyoto. Lyon immediately began producing a new suite of prints for the show. As he worked, he began pushing himself to create even larger prints, but doing so wholly by hand was becoming less feasible because the long hours of carving and printing (he hand-printed more than 18,700 individual impressions between the invitation in 2003 and the show in 2004) were causing increasing physical problems for him.

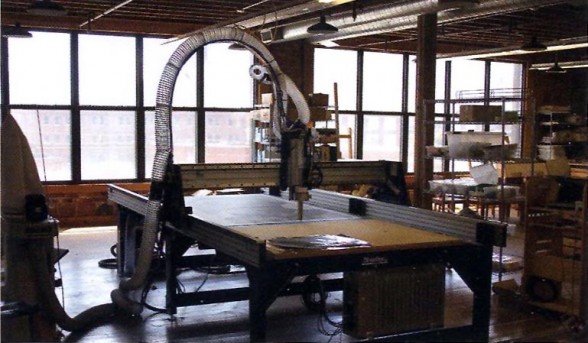

He knew that inkjet printers and photo polymer plates offered a potential way to continue working and increase the scale of his prints, but the process seemed to sacrifice so much of what he found compelling in the final images. From selecting, raising, brushing or otherwise altering the grain to changing the absorbency of the printing areas of the matrix, or creating subtle areas of gradation through delicate carving, it was clear that woodblocks were a central component of his printmaking. For years, Lyon had ‘considered building something akin to a computercontrolled Etch-a-Sketch in order to experiment with painting. When I came across an ad for ShopBot in a woodworking magazine, it fired my imagination for carving larger blocks by router’ After looking at the software and realizing that the ShopBot CNC router offered a path forward, he decided to invest in one. The influence was immediate, allowing him to complete a suite of 13 images from hand-carved blocks and another 13 images from machine-carved blocks for his solo show. Ultimately, the new approach had a profound effect on his art practice as a whole, sparking a flurry of new creative questions and avenues for his work.

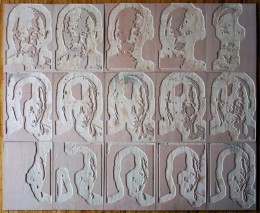

Figure 164. Overhead view of the 15 cherry blocks used for the printing of Anthony, by Mike Lyon. Image courtesy of the artist.

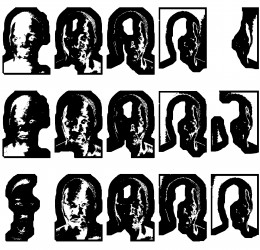

Figure 165. Digital image of 15 pre-production images used for the carving of 15 cherry blocks used in the printing of Anthony, by Mike Lyon. Image courtesy of the artist.

One of the first prints that integrated CNC carving was Anthony, a 76 x 53 cm (30 x 21 in.) print created from 15 cherry blocks. The techniques Lyon developed for utilizing the CNC router expanded his existing workflow for deriving multiple carving guides from photographs. The 15 blocks used to print Anthony are shown in Figure 164. Compare this to Figure 165 – thumbnails of the original photograph processed into individual bitmap images, just prior to being converted into tool-paths for the CNC router. The images in the thumbnails were created in Adobe Photoshop, and represent a close range of individual luminosity levels extracted from the continuous tones of the photograph, each of which will be carved on separate blocks. Through extensive experimentation, Mike has determined how many levels of luminosity and subsequently how many blocks are required to achieve a photographic, painterly, or less easily deconstructed rendering.

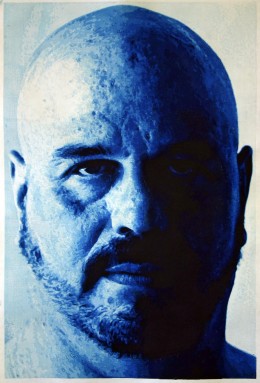

Figure 166. Mike Lyon, Rod, 2004. Size: 76 x 53 cm (30 x 21 in.). 16-block woodcut, printed in an edition of 12.1mage courtesy of the artist.

Figure 167. Portable Humidrawer system by Mike Lyon. Note the counterweight-balanced drawers on the left of the image, which are operated by foot control. On the right-hand side of the image, the printing area is actually a plenum with a vacuum surface to hold the block down and keep it extremely flat and in register. A vacuum suction tube exits below the printing area and off to the left to an out-of-shot industrial vacuum. Image courtesy of the artist.

Notice how throughout the Anthony blocks shown in Figure 164, there are islands of wood that are not visually represented in the final print. These islands provide paper support and are not inked during the printing process. Along with kento (registration notches), these areas must be added to the bitmaps after the image has been prepared and divided into its component layers of luminosity, shown in Figure 165. During a visit by the authors to his studio, Lyon points out that when creating the first series of prints with the CNC router, he was interested in creating a dramatic inner glow that required the minimization of attention to contours between layers. This is evident in Anthony and can also be very clearly observed in Rod, another of the portraits from 2004, shown in Figure 166.

Figure 168. One of 12 woodblocks for Aspen Grove, by Mike Lyon, during carving on a Shop Bot CNC router. Aspen Grove is a reduction woodcut -there was only a single block, carved and re-carved in stages, with a printing after each re-carving. In this photo, the carved areas (which are blue) were carved prior to the next printing -new carving is evidenced by lighter areas of the block. Image courtesy of the artist.

The introduction of the CNC router into the printmaking studio helped Lyon to expand image size and address mounting issues of fatigue, but it also introduced practical problems. Particularly, the larger size and increasing numbers of blocks began to generate difficulties with regard to keeping paper damp for long periods of time and with the handling of large pieces of thin, damp paper. Coupled with the fact that he does not work with assistants, some mechanical solution seemed necessary. To Lyon, the answer was to design a specialized vacuum table to hold blocks flat during printing. This table also integrated a specialized humidor to keep paper damp within a sliding drawer that delivered the paper directly over the block. The drawer was controlled by foot pedal, and allowed him to create these prints alone. He called this apparatus the Humidrawer, and it proved essential.

The impact of the CNC router and the Humidrawer on his productivity was dramatic. Lyon comments that all of a sudden, he ‘could work at printing a set of blocks while his machine assistant was busy carving the next set: His inventive solutions and unique workflow allowed him to complete the series of prints for his solo show in Kyoto, and it would eventually lead to experimentation with new approaches towards generating the printmaking matrix as well as new approaches towards painting and drawing. In the meantime, he was interested in increasing the scale of his prints even further and refining the Humidrawer system.

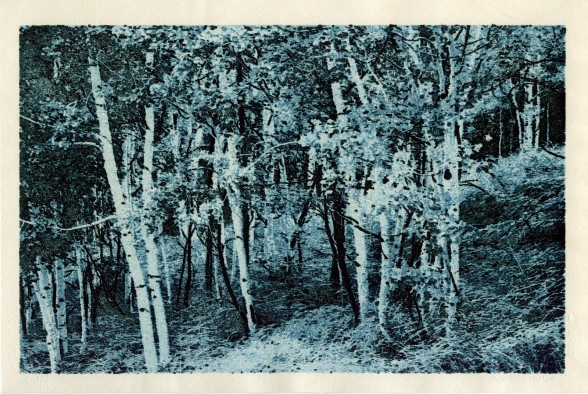

Figure 169. Mike Lyon, Aspen Grove, 2007. Size: 38 x 25 cm (15 x 10 in.). Printed by Shinkichi Numabe. Published by Mokuhankan. Image courtesy of the artist and David Bull of Mokuhankan.

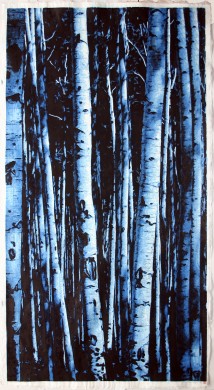

Figure 170. Mike Lyon, Aspen Grove, 2006. Size: 195.5 x 107 cm (61/2 x 12112 ft.). 12 woodblocks printed in an edition of six. Image courtesy of the artist.

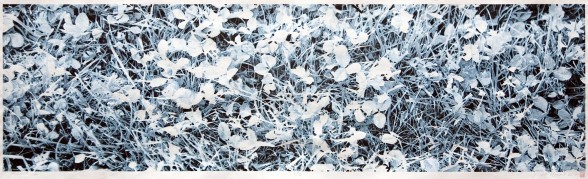

Since his CNC router was capable of carving full 122 x 244 cm (4 x 8ft) sheets of wood, Lyon was prompted to create an even larger Humidrawer that utilized a garage door opener for the linear motion system in place of the counterweight. Additionally, this version of the device integrated a self-designed and built pinch-roller press with a stationary bed, which allowed him to work with enormous paper, printing from blocks up to 122 x 244 cm (4 x 8ft). The large Humidrawer and woodblock press shown in Figure 171 demonstrates a number of improvements from the previous version, including an additional drawer for receiving printed states that does not interrupt the flow of paper through the system. Mike has used this updated version on many of his largest prints, including Sara Reclining, Aspen Grove and Grass 2.2. The successful integration of the CNC router into his studio practice inspired Lyon to consider expanding the capabilities of the machine. Perhaps due to his background in factory automation, he approaches the CNC device as an electromechanical platform that can be adapted for his needs. This adaptability offers an opportunity to expand, re-map or otherwise modify the capabilities of the router while retaining the aspects of CNC that are valuable for a given technique. Replace the router with a pen and you have a CNC drawing machine; replace it with a needle and you have a CNC drypoint machine. This is not to suggest that the replacement is trivial, but Lyon modestly points out that he has not invented anything when he designs a new headstock for his ShopBot. Of course, the results, seen in his artwork, are hard to mistake for anything other than a generous application of expertise and ingenuity. Lyon’s experimentation has resulted in a diverse number of artworks including drawings, paintings, and even mezzotint-like intaglio prints as shown in Figure 174 (overleaf). The idea of using the machine to create mezzotints required the design of a number of custom attachments-some to roughen the surface of the plate similar to the hand-rocking process, others that would allow him to burnish. In Figure 175, you can see three custom attachments for the ShopBot in which a roulette, drypoint needle and ball burnisher are mounted within a length of plastic pipe. These pipes are almost the diameter of his router’s mount, so he is able to utilize the existing headstock for holding these tools in place. Additionally, these tools are mounted in their pipes in such a manner that they have some downward tension, so that if there are minute variations in the flatness of the plate, the tools will still push into the material. Lyon used the roulette and drypoint needle to scratch parallel lines, tightly packed together, on a copper plate. Then, he would rotate those lines and scratch again, repeating this process several times until the entire plate had a uniform roughened surface.

Figure 171. Time-lapse view of Mike Lyon printing Grass 2.2 in the summer of 2010, using his large Humidrawer system, which incorporates the linear motion system from a garage door opener to deliver dampened sheets of paper to the pinch-roller press. Note. in the lower right section of the image, a receiving drawer for the most recently printed state. Image courtesy of the artist.

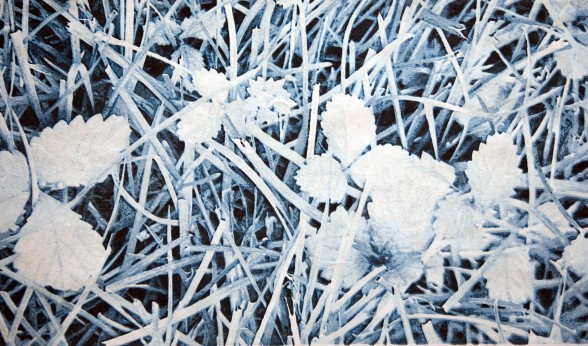

Figure 172. Mike Lyon, Grass, 2010. Size: 183 x 57 cm (72 x 22112 in.). 16 woodblocks printed in an edition of four. Image courtesy of the artist.

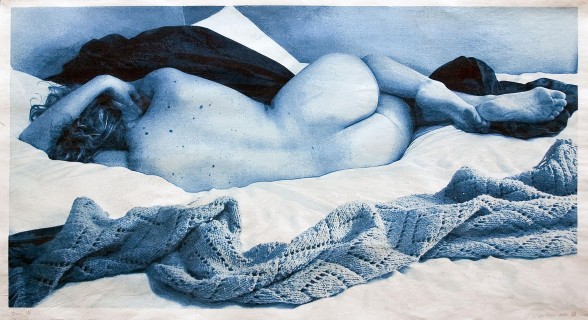

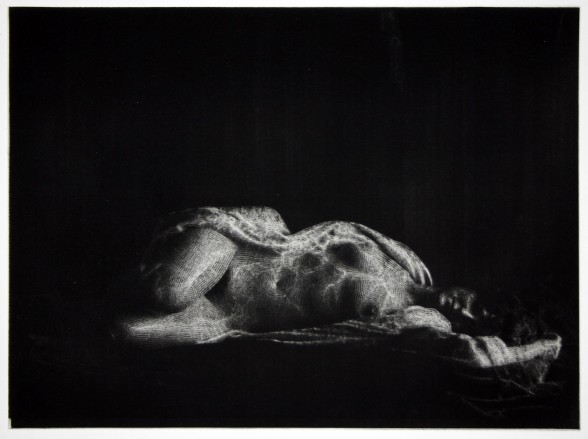

Figure 174. Mike Lyon, Sarah Reclining, 2005. Size: 23 x 30 cm (9 x 12 in.). Mezzotint proof printed by Anthony Kirk, Center for Contemporary Printmaking, Norwalk, CT. Image courtesy of the artist.

Figure 175. From left to right, drypoint needle, roulette and ball burnisher- each of which is mounted in an 11 cm (4’12 in.) tube that can itself be mounted on Lyon’s ShopBot CNC router. These tools were used in the creation of the Sarah Reclining mezzotint plate. Images courtesy of the artist.

Figure 176. Copper mezzotint plate, 23 x 30 cm (9 x 12 in.), used for the Sarah Reclining print. Image courtesy of the artist.

Once the dark background tone had been established, Lyon switched over to a custom burnishing attachment to bring out the light tones. Again using tool-paths created by separating a photograph into a number of individual luminosity levels, he began by burnishing the plate from light to dark tones. In this case, though, he prepared the tool-paths so that the machine would overdraw lighter areas each time. So, if there were 24 levels of luminosity in total, the lightest area would be burnished 24 times. The result of this process, which took nearly a month of continuous burnishing, is shown in Figure 176, the plate for Sarah Reclining.

The resulting image has mezzotint-like qualities, such as the rich, dark tones from which the figure emerges-but the process introduced a number of technical challenges. First. working the plate for that length of time began to harden the surface to the point that it was beginning to crack, and tiny flakes would be dislodged. Also, the threaded rods that move the machine’s headstock up and down began to develop wear from the unusually prolonged repetition. While the problem of material breakdown could be addressed through tool-paths, the issue of machine wear was more problematic.

Figure 177. Large ShopBot router at Mike Lyon’s studio in Kansas City. The router is set up to hold an ink pen that is raised and lowered via a custom solenoid headstock designed by Lyon. Image courtesy of the artist.

Regarding the unforeseen challenges posed by integrating CNC machines into his practice, Lyon remarked, ‘You really have to have confidence that you’ll be able to solve engineering problems when they arise.’: This is certainly the case with Lyon’s latest series of portraits-enormous, larger-than-life size pen and ink drawings-which utilize the ShopBot. For this series, he developed a solenoid-driven pen that allows him to create hundreds of thousands of Z-axis movements, but without wear and tear on the rack and pinion, an innovation that came about specifically because of his experiences with creating plates for mezzotint-like images. These enormous portraits, which require miles of drawn lines to complete, would not be possible without this. Though he plays it down, Lyon’s ability to use his engineering expertise in conjunction with his art practice provides him with the ability to create artworks with CNC technologies without becoming too enchanted with the means of production. This sober perspective is critical. As soon as one sees that the ShopBot is no more or less important than the brayer or burin, etching press or etching tank, work in the studio can uncompromisingly focus on the ideas embedded in the artwork itself. Lyon’s facility with his tools. and the years of experience spent honing them to his needs, certainly provide him with that clarity.

Figure 178. Mike Lyon, Joel, 2011. Size: 221 x 114 cm (87 x 45 in.). Drawing in black ink and white ink on heavy watercolor paper tinted with quinacridone and carbon black pigments. Image courtesy of the artist.