Tracy Abeln

March 25, 2013 – Tracy Abeln is an independent arts and entertainment reviewer whose work frequently appears in The Pitch Weekly newspaper (the Pitch published an abbreviated version of Tracy’s review):

It’s necessary to know the rules in order to be able to break them. Poetic license is an earned privilege, not a right. Just as Picasso’s early traditional painting provided a solid foundation for later forays into then-uncharted visual territories, (classical oil painting giving way to shattered-image views, macro-pixilated scenes and Cubist constructions), Kansas City printmaker Mike Lyon has established himself as a master of techniques by embracing technology to produce striking, larger-than-life portraits of people and nature.

Lyon has trained machines to do his mark-making. Inside an unassuming three-story building near the intersection of Southwest Boulevard and Broadway, a couple of ShopBots are busy at work following the programmed instruction of a human with two art degrees. One router machine spends time cutting away at plywood that will be inked into prints, another traces its X-Y coordinates in topographic-looking patterns with either black or white ink pens onto watercolor paper the living artist has tinted by hand.

A collection of drawings made by the latter machine — following automated millions of lines of instructions programmed by Lyon — are on display in a solo show at Sherry Leedy Contemporary Art through April 27th.

If you went to the much-touted “America: Now and Here” exhibition put on by Eric Fischl in the summer of 2011, you’re already familiar with Lyon’s larger-than-life head portraits; no, not the Chuck Close or Al Gore — the other one. Of course Close’s processes have had their influence; Lyon takes inspiration from Leon Harmon, Ken Knowlton, Claude Mellan and others.

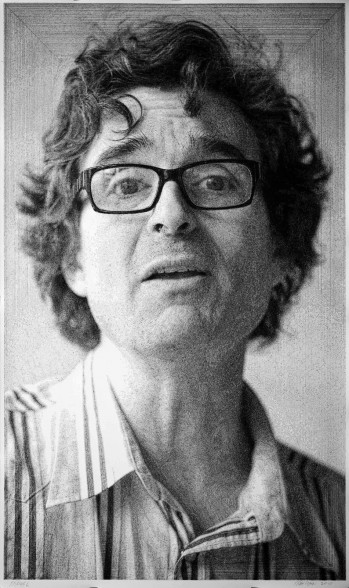

In the current show, simply titled “Post-Digital Prints and Drawings,” 10 seven-foot portraits of the faces of friends, intriguing strangers and well-known local artists act like frozen conversations; Lyon takes his own photographs then selects shots that offer moments of insight. Michael Rees looks like he’s on the verge of agreeing with you; Archie Scott Gobber is acting out a tongue-in-cheek reference to his double-entendre word-paintings; and Miguel Rivera is perhaps getting ready to explain some printmaking concept to his KCAI students.

Lyon recently hosted Rivera’s class at his studio, showing them how the carving machine systematically removes wood from a series of large, thin printing blocks, each one with a different layer removed before getting inked and pressed onto paper.

A visit to Lyon’s studio is a delight; he’s a natural teacher, enthusiastic about showing you his past, present and works-in-progress. If you’re lucky and there’s time, you might also get to see some of the ukiyo-e prints from 17th-century Japan that help inform some of his aesthetic.

In the late 1990s Lyon studied woodblock printmaking under Hiroki Morinoue in Japan, and he’s practiced and taught Shotokan karate for decades. The ground floor of his studio is a gorgeously appointed dojo and home to the Kansas City Shotokan Karate Club, in fact.

After about 15 years as an entrepreneur in the commercial sector, Lyon was able to devote himself full time to making art. That was 21 years ago, but though Lyon has the life experience of someone who grew up protesting — and getting tear-gassed for — America’s war involvement in the Vietnam, he retains a fresh enthusiasm for his work, spending between eight and 11 hours a day (including weekends) programming, printing, experimenting and refining techniques to build ideas into pictures.

Discipline and dedication pay off. He’s been exhibiting his work since 2001, in solo shows since 2004. His work is the subject of a chapter in the 2012 book “Post-Digital Printmaking: CNC, Traditional and Hybrid Techniques” by Paul Catanese and Angela Geary, and out of the Fischl connection grew his inclusion in the Kansas City Collection as well as a few significant sales.

Some of that attention stems from the fact that he has a website that is very detailed compared to many other artists: complete histories, essays, descriptions of technique — even including the sharing of computer code — back up visual libraries; new work is constantly being announced.

Still, he says it’s clear he needs to get out more. The work at Sherry Leedy’s gallery represents less than half of recent prints that are framed, ready to go yet are unseen in person except by a few guests. Like many artists, he says there’s something to wanting to be a “rock star,” being loved by cheering multitudes, but that it’s difficult to integrate the tasks necessary for self-promotion.

“The problem is,” he said, “these activities are different. That is, there’s making stuff, and then there’s selling stuff, and, maybe there’s also exhibiting stuff — but they’re different, and the skills involved and the motivations are different, so, like I said before, I really like making stuff, I’m driven to make stuff, I’m not nearly as driven to sell stuff.”

His technical training allows him to solve the problems of creating large-scale images through programming. The prints at the gallery do not include anything from his grasses or trees series, but are exclusively about the human figure.

Lyon’s motivation is not just technical but scientific; he’s intrigued by why certain things, such as the human form or face or a particular arrangement of pattern, look beautiful or evoke a positive emotional response, while others, even if made up of the same elements, do not.

“Some of the content I’m free to explore is how to make image, the ‘location of meaning thing,’” he said. “These heads six-foot high are recognizable, so where, how does that happen that I can squiggle lines on a paper and it looks like something, how to make a pen, how to make an image, how to make areas of light and dark?”

Although the glass frames present a boundary and the typically frustrating element of gallery-glare, it is worthwhile to step close to these prints and get lost in those etching-like squiggles. Stepping back, the eye then tells the brain to see shading, forms, a “real” picture of a face.

In two smaller works, the fact that there is less surface area available to convey detail means the eye-brain transmission is automatically filling in lines that are not there. In a long rectangular print of 16 little jumping Peregrine Honigs (dressed in signature bunny ears), outlines to the figures are missing in some places, yet, of course, you perceive completed form. Lyon said that Caleb Taylor’s work, which is in a solo show in the rest of the gallery, also plays with this idea of layers and looking behind them: in real life, we can tell there’s a tiger hiding in the bushes without having to see the whole animal at once.

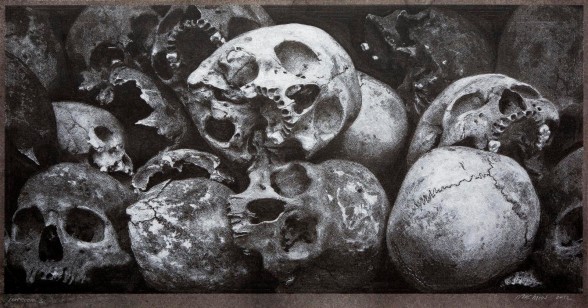

Amid drawings that for the most part are life-filled (a couple the expressions on people’s faces suggest brooding or even pain), a haunting print of a pile of human skulls is on a short wall all by itself. The skulls are about life-size, and as you walk by, your own face is reflected on them. This is Lyon’s response to a recent visit to Cambodia; the photograph is from S21, a school that the Khmer Rouge used as a prison for supposed enemies of the state. Only seven individuals of the thousands tortured there survived. The skulls are among the 10,000-plus dug up in the associated killing field.

Although Lyon believes that the three prints he made of this subject are pale, inadequate responses to the intense experience of being at the site, he says that the one up at the gallery is perhaps technically the best drawing he’s made. Its balance of black and white lines, the particular warm color of the pigment it’s drawn on work together well for him.

“I love how some is dark and ghostly, and some of it is crispy-contrasty; there’s a nice balance, a visual balance. It’s a beautiful drawing of a subject of horror, kind of the opposite of ‘Maggie.’”