242 S. Santa Fe

Salina, KS, 67401

785.827.1431

info@salinaartcenter.org

Salinaartcenter.org

Exhibition walk-through

The XYZs of Post-Digital Gesture: Drawings & Prints by Mike Lyon

January 18 – April 16, 2017

Mike Lyon’s work is not digital art. Lyon is a pioneering figure in the emergent field of post-digital printmaking and graphics. [The first major study of the subject, Paul Cantanese’s and Angela Geary’s Post-Digital Printmaking: CNC, Traditional and Hybrid Techniques, was published in 2012 and devotes an entire chapter to Lyon.] Combining traditional art materials and techniques with automated machine tools and digital technology from the realm of industrial manufacturing, Lyon has developed innovative processes for making his images.

Although the path along which his visual ideas travel from conception to realization is strikingly inventive, the materials and techniques he uses to realize their final form are centuries old. Lyon’s pictures are made with ink and paper, printed from wood blocks and copper plates, or drawn with a pen. They are not output from inkjet printers, displayed on monitors, or projected on screens. It is his use of digital processes in the service of creating images wrought by analogue means that defines Lyon’s work as post-digital.

Printmaking is, by nature, a hybrid activity. Printmakers have always adapted the latest technology to existing traditional studio practices. Lyon’s use of digital technology and robotic machinery is brilliant, masterful, but judicious. He is not seduced by the gee-whiz-bangness of the tools he employs, the uses of which are always subservient to his art. Lyon’s machines operate with his proxy. His instructions determine their every move along the X, Y, and Z axes and result in an expressive gesture distinctly his own.

WHAT IS POST-DIGITAL?

The term “post-digital” has recently come into use to refer to an emergent class of printmaking and graphic art. The term does not imply that post-digital work and practices are free of digital technologies and processes. Quite the contrary, artists who work in a post-digital mode exploit digital technology and automated machine tools in creative and innovative ways. The difference between post-digital work and digital art is the way in which the completed object is realized. For our purposes, post-digital work is that which, in the words of author Sylvie Covey, has been “produced through physical interaction with a transfer mechanism” (e.g., printed under pressure with a press or drawn with an ink pen or other stylus).

INTRODUCTION

Mike Lyon’s application of digital technology to his art making is rooted in his experience with his family’s business. In 1976, after completing his art studies (BA, art and architecture, University of Pennsylvania, 1973 and BFA, painting, Kansas City Art Institute, 1975), Lyon went to work for the cattle hide processing operation his great-great grandfather started in Kansas City. While there, he invented a computerized system to automate the labor-intensive process of grading cattle hides. Soon after he founded Grading Systems, a computer hardware and software design business. Under the artist’s direction, Lyon’s company developed ROBO-PIC, an award-winning computerized system for automating order fulfillment in large warehouses, which worked by using remotely controlled dispensers to place items in containers moving along a large conveyor belt. In 1991 he sold the business and returned to the studio the following year, where he has been making art full time ever since. His innovative developments in automation with Grading Systems and ROBO-PIC are conceptual forebears of his current art practice.

Lyon’s contributions to the field of post-digital printmaking and graphics revolve around his use of a CNC (computer numerically controlled) router, a large industrial machine originally designed for commercial woodworking applications. Computer coded instructions direct the router’s bit along the X (length), Y (width), and Z (height) axes as it carves out designs from a sheet of wood on the machine’s bed below.

Lyon’s idea was to adapt the CNC router to carve blocks for his woodcut prints. First, he developed procedures to extract information from digital image files and convert it into a language the CNC router understands. With this code the artist can program the CNC router to carve blocks to his precise specifications. Though digital technology is used to create the wood blocks from which Lyon’s images are printed, the prints are made using the centuries-old method of printing ink on paper under pressure using a press or other means. In this way, Lyon’s prints are said to be post-digital.

In 2006 Lyon began experimenting with retrofitting the CNC router assembly with an ink pen. The artist’s computer-generated code guides the trace of the pen in the same manner Lyon’s code directs the router bit to carve his blocks. This has enabled him to produce enormous drawings comprising many layers of intricate marks. The time and effort necessary to create his work is as monumental in scale as the drawings themselves. The larger works require tens of millions of lines of code and can take up to several weeks of continuous drawing to complete. Lyon has also modified a CNC machine to produce acrylic paintings using a similar process.

Note: All work is by MIKE LYON (Born 1951 in Kansas City, MO), lives and works in Kansas City, MO, and is courtesy of the artist unless otherwise indicated.

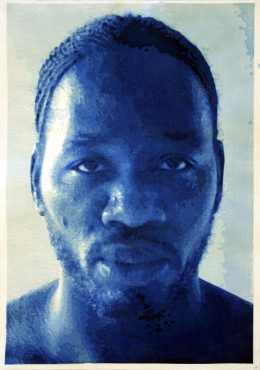

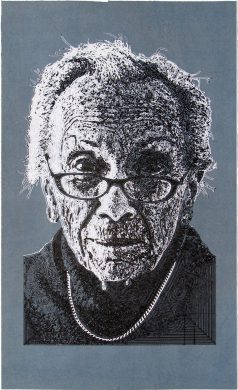

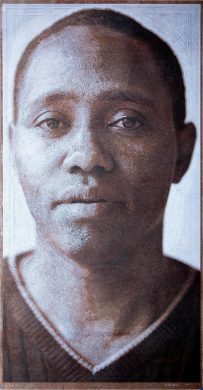

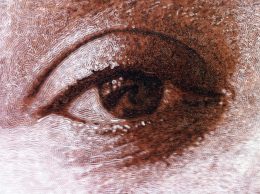

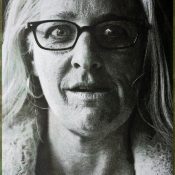

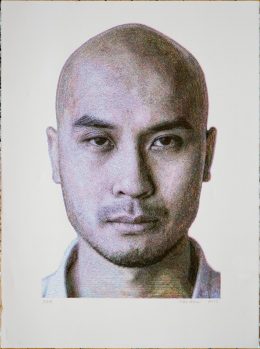

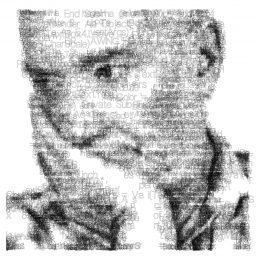

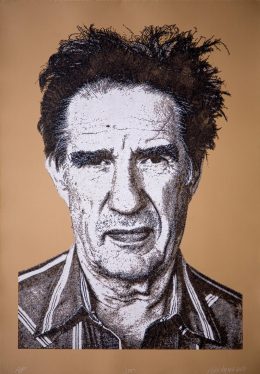

Anthony is the first print Lyon made using a CNC router modified to carve wood blocks for his relief prints. Prior to automating his carving process, Lyon cut his blocks by hand, creating prints using traditional Japanese printmaking techniques. Often, his color woodcuts were 15 x 10 inches, or ōban-sized, a standard traditional Japanese format. Aside from the scale of his pre-CNC imagery, Lyon’s earlier hand-carved prints are nearly indistinguishable from those created using the machine.

Anthony was printed in Prussian Blue from fifteen cherry plywood blocks. Lyon used the Japanese technique of repeated printings in shades of blue, or aizuri-e (blue printed pictures), popularized in Japan in the 1820s with the availability of Prussian Blue, a stable and lightfast synthetic pigment imported from Europe. The print’s format also draws on traditional Japanese pictorial conventions. The subject’s head is placed close to the picture plane and nearly fills the frame, recalling the tradition of ōkubi-e (big-head pictures).

The division of labor among Lyon, the computer, and the CNC machine recalls the working methods of Japanese ukiyo-e printmakers active between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries. In this tradition, the artist developed a schematic sketch of the image with color annotations. Then, an artisan carved the blocks, which were given to yet another person to print. Finally, a fourth party published the completed prints. Typically, history records only the names of the artist and the publisher.

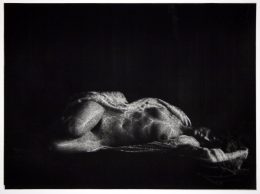

Mezzotint, a printmaking process dating to the mid-seventeenth century, is the earliest graphic technique for printing tone. Popular as a method of reproducing paintings in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, particularly in England, mezzotint is little used today.

The surface of a copper plate is uniformly roughened using a tool with many small teeth or other mechanical means. If inked and wiped at this stage, the plate will print solid black. Images are created by burnishing areas of the surface selectively. The more an area is burnished, the less ink it will hold, and the lighter it will print. An area burnished completely smooth holds no ink and thus prints white. This manner of working from dark to light enables the artist to create mid-tones between white and black, hence mezzotint (Italian for “middle tint”).

Lyon automated the plate preparation and burnishing process by designing three attachments for his CNC machine: a drypoint needle, roulette, and ball burnisher. He roughened the plate using the machine to scratch closely spaced parallel lines across the entire surface with the drypoint needle, rotating the angle of the lines and repeating the process until the surface was uniformly roughened. Then, Lyon’s code directed the ball burnisher to smooth areas of the roughened surface.

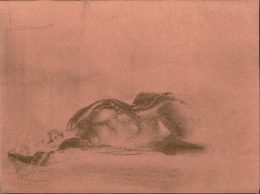

4. Sara (Sara Reclining), 2006, color woodcut on paper, 42 x 77 in., KSU, Beach Museum of Art, Friends of the Beach Museum of Art purchase, 2007.23

Printed in Prussian Blue from seventeen blocks using paper Japanese Living National Treasure Iwano Ichibei made especially for Lyon, Sara (Sara Reclining) is the artist’s most ambitious color woodcut to date. The complexity and scale of the print presented challenges that required the artist to engineer innovative solutions.

The large number of blocks complicated the task of maneuvering the large sheet of paper during the printing process. Each block required a separate pass through the press in perfect register with the others. Lyon designed and manufactured a complex, large-format woodcut printing press with a five by ten feet bed. Before printing, the paper must be dampened in a humidor drawer below the press bed. To carefully deliver the sheet from drawer to press and back with the printing of each block, Lyon built a system adapting components of an electric garage door opener. The dampened sheet is moved from the humidor drawer to a similar humidor drawer above the press bed. When operated, the top drawer cantilevers over the press bed (closing the garage door). As the drawer retracts (opening the garage door), the paper is gracefully laid on the block’s surface.

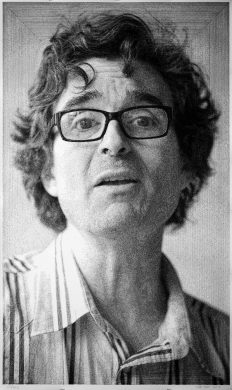

5. Jim, 2007, lithograph on paper, 37 x 26 in., KSU, Beach Museum of Art, Friends Kansas Art Fund, 2008.104

Master Printer Mike Sims printed Jim at the Lawrence Lithography Workshop. The image, printed on tan paper, required seven plates, one to print the brown background over the entire sheet, three with transparent white ink and three with transparent black. The way in which Lyon constructed this image out of black and white on a mid-value colored sheet of paper anticipates the later, large-scale drawings in black and white ink on pigment-tinted paper on view in the Reception Gallery.

Lyon started with code he generated for execution on the CNC machine. He then wrote a program to convert it into AutoCAD DXF files that could be loaded into Adobe Illustrator and used to make film positives from which the lithographic plates could be made.

The subject of this painting is the artist’s father. A similar portrait of his mother hangs on the adjacent wall. To create these two images, Lyon modified his CNC machine, replacing the router bit with a flow pencil, a pin-striping tool which delivers paint by gravity through a valve Lyon controlled via his computer programs.

This portrait of the artist’s mother is a pendant to the painting of his father which hangs on the adjacent wall. The photographic source of this image is also the basis for Lyon’s drawing WOWMOM, also on view in this gallery.

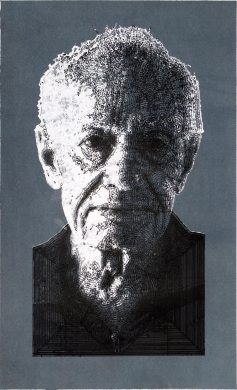

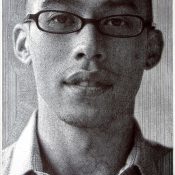

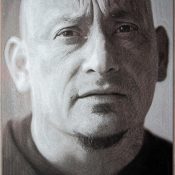

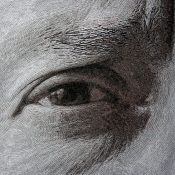

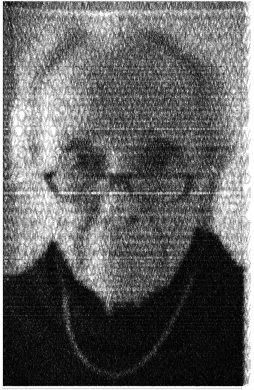

The subject of this portrait is Kansas City-born sculptor Michael Rees, a professor at The William Paterson University of New Jersey. It is representative of Lyon’s large-scale pen and ink drawings produced with a single color of ink (black) on white paper using a CNC machine.

Over the course of millions of lines of code and several weeks, Lyon’s machine built up the image by drawing layer upon layer, all of which resolve to form a cohesive image. In many of Lyon’s drawings created in this manner, no two lines in a single layer intersect.

- 11. Chandler, 2010, pen and ink on paper, 84 x 45 in.

- 12. Chandler, detail

Danson is one of Lyon’s earliest successful attempts to introduce a second color of ink (white) in his drawings. In Danson, as in his lithograph Jim and the portraits of the artist’s parents, Lee and Joanne (all on view in this exhibition), Lyon combines black and white lines against a tinted ground.

- 15. Carlos, 2012, pen and ink on pigment-tinted paper, 75 x 45 in.

- 16. Carlos, detail

- 17. Misty, 2012, pen and ink on pigment-tinted paper, 82 x 45 in.

- 18. Misty, detail

- 21. Maggie, 2012, pen and ink on pigment-tinted paper, 85 x 44 in.

- 22. Maggie, detail

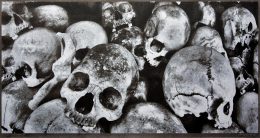

Cambodia 2 is part of a series of three drawings depicting the aftermath of the atrocities committed in the Khmer Rouge Killing Fields between 1975 and 1979. The human skulls are part of a display at the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum in Phnom Penh, the capital of Cambodia in Southeast Asia. The museum is a memorial to the victims of the Khmer Rouge regime’s campaign of state-sponsored genocide during which it is estimated that as many as 2.5 million persons were brutally tortured and put to death. The site of the museum is a former high school that was converted to Security Prison 21 (S-21), one of approximately 150 execution centers throughout the country.

The richly mottled background of Addy and Arthur is the result of tinting the paper with black, yellow, blue, and magenta pigment before drawing the image in black and white ink. The paper on which Addy and Arthur is drawn is particularly heavy and absorbent, thus rendering the single layers of white ink nearly transparent.

Dinh is drawn in five colors (black, blue, red, yellow, and white) on an untinted sheet of paper. Lyon made several attempts at this drawing before it was successful, experimenting with the order in which the colors were drawn. Ultimately, working blue, red, yellow, black, and white proved to be the solution.

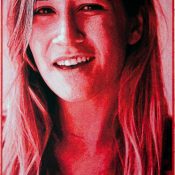

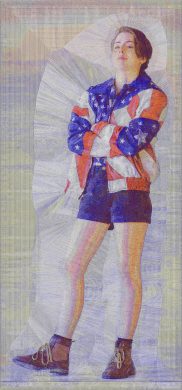

The subject of this portrait is Carrie Riehl, a Kansas City-based artist, editor of Bohemian magazine, and Lyon’s former studio assistant. This print is one of two works in the exhibition that can be considered purely digital art. It was not drawn with a CNC machine or printed under pressure on a press. Rather, it was output as an inkjet print from a digital file, much in the same way a digital photograph is printed.

Lyon extracted information from his photographic source and converted it to code for his CNC machine. He then modified one of his computer programs to convert the sixty layers of information into sixty DXF files, a CAD (computer-aided design) file format used with software such as AutoCAD. These files were loaded into Adobe Illustrator, where they were stacked, color and transparency applied, and then flattened to create a single file which could be further manipulated in Adobe Photoshop before printing.

29. The code that moves the pen that makes the image – I wrote the code – the image is mine, 2014, pen and ink on pigment-tinted paper, 62 x 45 in.

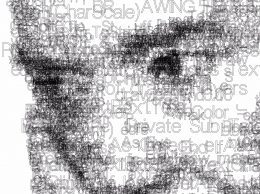

Lyon’s title for this drawing stakes a claim of authorship. This self portrait, drawn in black and white ink, is an example of what Lyon refers to, somewhat tongue-in-check, as “iteratively self-referential programmatic art.” The drawn lines in the image are not the usual concentric squiggles that compose most of his drawings. Rather, they form text, numbers, and punctuation drawn in a single typeface and varying in scale. The source of the drawn characters is the machine code of the computer program Lyon generated that guides the CNC machine.

A similar, smaller drawing in black ink is on view in the adjacent gallery.

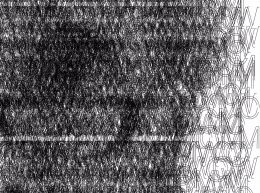

This portrait of the artist’s mother was created in the same way as Lyon’s The code that moves the pen that makes the image – I wrote the code – the image is mine also on view in this gallery. Instead of computer programming language, Lyon has used the text “WOWMOM” drawn repeatedly to create the image.

This self portrait is an example of what Lyon refers to, somewhat tongue-in-check, as “iteratively self-referential programmatic art.” The drawn lines in the image are not the usual concentric squiggles that compose most of his drawings. Rather, they form text, numbers, and punctuation drawn in a single typeface and varying in scale. The source of the drawn characters is the human-readable source code of the computer program Lyon wrote to generate the machine code that guides the CNC machine.

A similar, larger drawing in black and white ink on pigment-tinted paper is on view in the adjacent gallery.

- Kelsey, 2015, pen and ink on pigment-tinted paper, 35 x 35 in.

- 36. Kelsey, detail

- Kelsey, 2015, pigmented inkjet print mounted on aluminum, 30 x 30 in.

- 34. Kelsey, detail

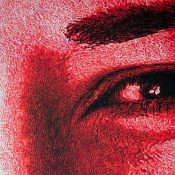

Kansas City native and Brooklyn-based illustrator and comics artist Kelsey Wroten is the subject of this drawing, a digital version of which hangs directly to the right.

After creating the drawing on view at the left, Lyon converted his code into digital files that could be loaded into Adobe Illustrator, a popular graphics editor. The resulting files, one for each layer of the drawing, were then combined to create a single file which could be further manipulated in Adobe Photoshop before printing with an inkjet printer. This print, like Lyon’s Carrie Americana, can be considered digital art because it was output as an inkjet print from a digital image file and not drawn with a pen on paper or printed under pressure on a press.

A comparison of the two versions of Kelsey is instructive and reveals an important difference between digital and post-digital art. In this version, digital information was translated into an equivalent graphic image. Lyon’s pen and ink version, on the other hand, was created through the physical action of the pen under the artist’s direction. Visually, the drawn version has an autographic character and sense of gesture not present in the digital version.

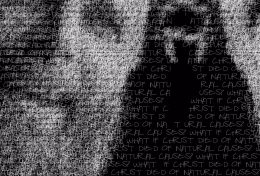

Rendered in white ink on tinted paper, this drawing is an example of Lyon’s “iteratively self-referential programmatic art.” Instead of using characters from a type font to create the image, as he did in drawings like WOWMOM and The code that moves the pen that makes the image – I wrote the code – the image is mine, Lyon used script based on his hand writing, posing the theological conundrum “What if Christ died of natural causes?”