- The Epsten Gallery Exhibition

- September 15 – November 29, 2019

- Cocurated by Mike Lyon and Elisabeth Kirsch

- Exhibition Catalog designed and produced by Mike Lyon. 137 full-color pages.

- Order Catalog at Amazon ($20)

INTRODUCTION

Look Me in the Eye: Portraits of Kansas City (September 15 through November 29, 2019), a juried exhibition of portraits by artists who live or work within a 60-mile radius of Kansas City.

This exhibition aims to acknowledge that the Kansas City area is a much more diverse community than many realize. To that end we agreed to an egalitarian selection process which encouraged the submission of portraits by artists of all ages, ethnicities and genders through a public call for entry. The call was posted to callforentry.org and epstengallery.org. Links to the call were regularly broadcast to the Kansas City Artists Coalition, the 2,500-member Kansas City Artists Facebook group, the 300-member Kansas City Artist Connection Facebook group, the 4,000-member Artist Community of Kansas City Facebook group, and were shared on numerous artists’ social media pages.

One hundred fifty portraits were submitted through this public call, and we agreed to accept 42 portraits by 42 artists. We invited 23 additional artists to submit work, making a total of 65 portraits in the exhibition. We intentionally set a high standard for the selection of accomplished and evocative work and hope you agree that the exhibition is amazingly diverse in approach to the portrait, scale, medium, subject, and message. We are very happy to exhibit portraits by some of our community’s most highly acclaimed and well-established artists alongside some spectacular work from emerging and mid-career artists, outsiders, and others who are not the “usual fare.”

Mike Lyon

Elisabeth Kirsch

September 15, 2019

Drawn to the Portrait

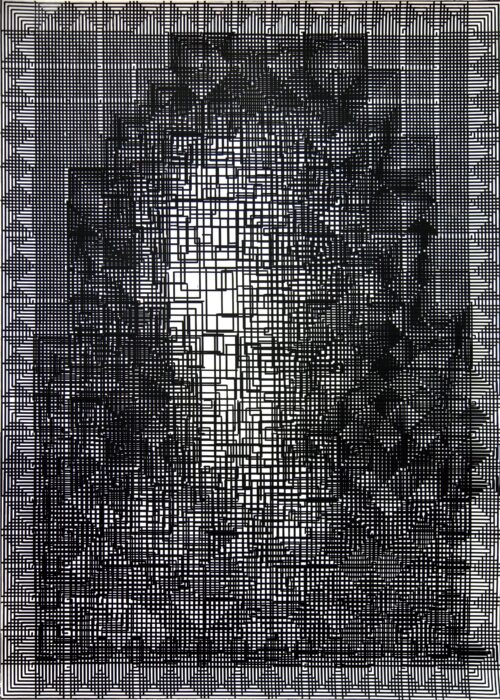

My own work is a long series of experiments in ways to communicate image through an unusual kind of mark-making. My process is complex and analytical and involves programming computers and building machinery to manipulate traditional art-making tools, materials, and imagery using non-traditional methods. I’m looking to the old while inventing (sometimes re-inventing) the new. I typically portray the face, figure, or botanicals like grass or leaves. The creative work is almost entirely conceptual, occurring inside my head. Because every mark, line, brush stroke, etc. is calculated in advance, I don’t get to see the results until the work is complete.

The computer programs I write will, at run-time, gather numerous parameters from me which control how the image will be produced; the size of the image, line width, spacing, whether I’m painting light on dark or dark on light, and especially a reference image. The reference image is usually my digital photograph of a family member, artist, or other friend. My programs use my parameters to riff off the reference image and then output additional programs which instruct the machinery how and where to move. I attach a pen or drypoint needle or paintbrush or airbrush (whatever) to the machinery and they leave tracks that gradually accumulate, layer by layer, and become my artwork.

For a portrait, I’ll usually shoot hundreds of photos of my subject while we chat, and then hope to find one or two which both call out to become art and have qualities which are compatible with whatever process I’m exploring. My process and approach evolve with each completed work. Each provides clues that lead me to some new approach. I haven’t lost interest after more than 25 years working this way.

Setting aside my own process and speaking generally, a portrait is a pictorial representation of a person, usually showing the face, the face being the single most distinctive cue to a person’s identity and mood, arguably our most important visual stimulus. There’s a special area of the brain called the fusiform gyrus which plays a crucial role in recognizing faces – if it’s damaged, then we can’t even recognize ourselves and the people closest to us. That condition is called prosopagnosia (face-blindness) and it has an obvious detrimental effect at all stages of life. We are literally wired up to “Look Me in the Eye.”

People have been making sculptural portraits for at least 25,000 years and realistic painted likenesses for 2,500 years or more. Self-portraits appeared early in 15th Century Europe as wealthy and powerful patrons increasingly commissioned portraits of themselves and their families. Portraits were very fashionable for centuries.

The world tilted a bit in 1839 with the birth of practical photography, and that same year, Robert Cornelius made the first American self-portrait photograph. Compared with painting, photography was (and remains) quick, cheap, and precise. As photography became ubiquitous, the art world tended to judge representation in art, and especially portraiture, as unfashionable if not irrelevant. In recent years, the portrait (and representation generally) has regained a measure of popularity and respect, thanks in part to the enthusiastic public reception of Amy Sherald’s fabulous portrait of Michelle Obama and Kehinde Wiley’s of Barack Obama, among others. Many artists whose work isn’t mainly portraiture continue to be interested in the portrait as art regardless of fashion – most of the works in the recent and spectacular “30 Americans” exhibition at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art could be considered portraiture.

Sandy Nairn, then-director of the National Portrait Gallery, London, summed up the relevance of portraiture in her June 1, 2006 lecture, Why do painted portraits still matter? this way:

“The fast-changing landscape of surveillance and the globalization of digital imagery calls for the counterpoint of intense, ‘local’ imagery contained within a painting. The possibilities of allegory and complex meaning are distinct: the symbolic realm can come to the fore. The conveying of character in a painted portrait is specific and dynamic. There is a process described through paint – an intensity to the relationship between artist and sitter – which produces a different character from the medium of photography. And it is this intensity, often freed from the conventions of previous periods, which gives a great portrait its authority. The painted portrait endures.”

It has been my great pleasure designing the call for entry, selecting work for this show, producing this catalog, meeting some of the artists, and especially getting to know my co-curator, Elisabeth Kirsch. Elisabeth’s devotion to ensuring that artists and submissions lived up to the quality and diversity we sought, her humor, deep knowledge, intelligence, amazing art collection – well, this has been the best time! We’ve had countless meetings by phone, email, and face to face at her home and my studio. She’s become a wonderful friend and we share a passionate belief in the relevance of the portrait.

Mike Lyon

Artist, teacher, curator

Why Portraiture Matters

“What is it about people that since the dawn of time we’ve wanted to mark our presence so that other people will see it?” – Chuck Close

Portraiture has played a vital role in the history of art since the ancient Egyptians depicted the Pharaohs and their minions on the inside of pyramids. People from around the world wait in museum lines longer than ever to see the Mona Lisa, Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon, and the portraits of Rembrandt, Vermeer, Velasquez, Van Gogh, and hundreds of other great artists through the ages. Photography may have robbed painting of its centuries-old grip on facial representation, but as Kehinde Wiley, who painted Barack Obama’s official White House portrait, notes: “In the 21st century, when we’re used to clicking and browsing and having constant choice, painting simply sits there silently and begs you to notice the smallest of details.”

In the 20th century, modernism – with its wild experiments in cubism, surrealism, and abstraction – freed artists formally, and psychologically, to expand the very notion of what constitutes painting. In so doing, the art of portraiture was also radically altered, and the psyche of the artist became as paramount, in the end product, as that of the subject.

Not that great portraiture was ever just mere representation. As Rembrandt lamented about his portrait commissions: “I can’t paint the way they want me to paint and they know that. Of course you will say that I ought to be practical and ought to try and paint the way they want me to paint. Well, I will tell you a secret. I have tried and I have tried very hard, but I just can’t do it! And that is why I am just a little crazy.”

And which is why Rembrandt also painted so many self-portraits. No one to complain, or withhold payment until the wrinkles are removed, or demand that the backdrop be painted another color. Francisco Goya is called “the last of the old masters and the first modern artist” partly because, as court painter to the Spanish royal family in the 1800s, his portraits were resolutely real as opposed to merely flattering. They are as riveting today as they were 200 years ago.

The artists in “Look Me In the Eye,” all living in the Kansas City region, have created portraits from drawings, watercolors, glass, textiles, and paintings that run the gamut from the traditional to the surreal to virtual abstraction. Some works are only a few inches in size; others are life-size. Some

artworks border on the ethereal; others are openly confrontational. Emotional content ranges from humorous to abject.

It’s impossible to lump any of the participating artists into neat categories. This is a survey of some of the best portraits made in the area, by artists who work in various disciplines and depict a variety of subjects. Straightforward portraiture is well represented by a wide variety of artists, including Tom Corbin, Jeremy Garton, Johne Richardson, and Julie Farstad. Self-portraits abound, and artists such as Sherry Cromwell Lacy, Steff Crabtree and Wilbur Niewald portray themselves unsparingly. Surrealism underscores the portraits by Anne Pearce, Michael Toombs, Kim Lindaberry, Fernando Achucaro, and others. Portraits by Mike Lyon, Ritchie Lynne and Jim Sajovic incorporate abstraction as part of their subject matter. There is ample supply of storytelling by Harold Smith, Elise Gagliardi, Sonie Joi Ruffin, Christopher Leitch, and Rachelle Gardner-Roe.

There is only one feature shared by all the artists in “Look Me In the Eye,” and that is punctum. The definition of punctum, as described by Roland Barthes in 1980, is art that stands apart from the generic due to the inclusion of such idiosyncratic details that it establishes a direct relationship with the viewer. It is similar, in some way, to being psychically charged. In short, artwork that is defined by punctum is unforgettable.

As surrealist imagist Wangechi Mutu says, “Art allows you to imbue the truth with a sort of magic, so it can infiltrate the psyches of more people, including those who don’t believe the same things as you.” All the artists in “Look Me In the Eye” have sprinkled their magic throughout every work. The viewer is never a bystander when they look at a portrait. They are staring, prying, and eavesdropping. Relationships are made, which is why portraiture still matters and always will.

Elisabeth Kirsch

Independent curator and writer

Exhibition Invitation

65 works by 65 artists curated by Elisabeth Kirsch and Mike Lyon

Fernando Achucarro, Ricky Allman, Ione Angilan, Rhonda Barber, Philomene Bennett, Joe Bussell, Ariana Chaivaranon, Tom Corbin, Steff Crabtree, Sherry Cromwell Lacy, Dominique Delgado, Ryan Delgado, Julie Farstad, Jessie Fisher, Barbara Florez, Aimee Fresia, Elise Gagliardi, Rachelle Gardner-Roe, Jeremy Garton, Tom Gomersall, Tanya Hartman, Jennie Haugen, Diane Henk, Corin Hoke, Peregrine Honig, Kwanza Humphrey, Jennifer Hutton, Robert Jinkins, Linda Jurkiewicz, John Keeling, Alex Krahenbuhl, Dean Kube, Sara LaGrand, Jim Lawrence, Christopher Leitch, Yue Li, Kathy Liao, Kim Lindaberry, Ritchie Lynne, Mike Lyon, Clinton Marstall, Michael McCaffrey, Jean McGuire, Wilbur Niewald, Melanie Nolker, Benjamin Parks, Anne Austin Pearce, Jason Pollen, Lonnie Powell, Johne Richardson, Jim Sajovic, Hasna Sal, Jon Schroeder, Roger Shimomura, Hyeyoung Shin, Chico Salvador Sierra, Harold Smith, M.C. Snodgrass, Chloe Sotomayor, Emily Stark, Sonié Joi Thompson-Ruffin, Rebecca Tombaugh, Michael Toombs, Mark Walter, Ryan Wilks